On Nov. 20, 2012, the day Rutgers accepted an invitation to join the Big Ten, prominent New Jersey sports columnist Steve Politi summed up the shocking turn of events thusly: “At long last, the Scarlet Knights have won a title. They are the National Champions of Realignment.”

With a wave of then-commissioner Jim Delany’s wand, Rutgers, the New Jersey school that famously won college football’s first game in 1869, magically escaped the crumbling Big East for the sport’s most lucrative conference. Even a decade later, with the Big Ten having now added four schools — USC, UCLA, Oregon and Washington — from the other side of the country, Delany’s decision to invite Rutgers was more controversial … and riskier.

Rutgers’ time in the Big Ten has been a competitive and financial nightmare, compounded by a few salacious scandals. Entering its 10th season in the conference, the football team has gone 13-66 in league play. Meanwhile, despite astronomical increases in shared Big Ten revenue, the athletic department has racked up more than $250 million in debt, according to financial documents obtained by The Athletic and first reported by NorthJersey.com.

Delany, who led the conference for 30 years, is largely credited as a visionary who touched off a new era in realignment by adding Penn State, later landing Nebraska and launching the Big Ten Network. But his 2012 decision to bring in mediocre football schools Maryland and Rutgers has not thus far stood the test of time.

Maryland, at least, has excelled in other sports, winning national championships in men’s lacrosse (2022, 2017), women’s lacrosse (2019, 2017, 2015, 2014) and men’s soccer (2018). Whereas in the 2022-23 Learfield Directors’ Cup Standings, which ranks schools’ overall athletics success, Rutgers finished 130th — 58 spots lower than the next-closest Big Ten program, Purdue.

“Rutgers had a good reputation, although they hadn’t lived in the big leagues,” Delany says. “In one moment, they thought they were Penn State. In another moment, they thought they were Bucknell. So they hadn’t made the investment.

“I consider it a long-term play, but I don’t feel like I need to defend it. … I knew that it would be a big climb to begin with.”

But just how long is the climb supposed to take?

“’I’ve seen this over and over and over again,” says Mark Killingsworth, a Rutgers economics professor since 1979. “There’s always something that’s going to get Rutgers out of this financial disaster, and bring Rutgers into the bright lights of big-time athletics. But it’s never happened yet.”

For one night, Nov. 9, 2006, Rutgers was truly New York’s college football team. The Empire State Building lit up red as the 8-0, 15th-ranked Scarlet Knights knocked off 8-0, third-ranked Louisville 28-25 on a last-second field goal, unleashing a massive field-storming in Piscataway. For sixth-year coach Greg Schiano’s program, it was the pinnacle of an improbable rise from a 1-11 record four years earlier and decades of futility before that.

That 2006 team – led by future Pro Bowl running back Ray Rice, NFL receivers Kenny Britt and Tiquan Underwood and NFL defensive backs Jason and Devin McCourty – finished 11-2 and a school-best No. 12 in the final AP poll. The Knights have not finished ranked since, but they were bowl-eligible in five of their last six seasons in the Big East.

“I was almost mad that something like (the Big Ten) couldn’t have happened while we were there,” says Jason McCourty, now an analyst for CBS and NFL Network.

But by 2012, Schiano had left for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, and the Big East was on the brink of extinction. A series of dominos that began when the Big Ten added Nebraska in 2010 led to West Virginia leaving for the Big 12 and the ACC taking Big East members Syracuse and Pittsburgh in 2011. Then the next year, Notre Dame, a football independent but Big East member in other sports, reached a similar deal with the ACC that included playing five football games a year against ACC foes.

The Big Ten’s Delany had been satisfied with 12 schools but saw demographics stacking up against his Midwest-based conference. The ACC had moved into the Northeast and Indiana. The SEC acquired programs in the second-most populated state (Texas A&M) and at the Big Ten doorstep (Missouri). Possible expansion candidates had left for other conferences.

“The Midwest was growing at less than 1.1 percent across the board,” Delany says. “The Sun Belt was growing at 4, 4.5 percent. So you could see where the future was going. Our students and our alums had moved away to the East Coast, to the Southeast and to the West Coast. And everybody else is in two, three, four regions. So while the problem may not have been immediate, it was inexorable.”

Delany saw Maryland as the linchpin to his next move. Coinciding with it, the commissioner targeted Rutgers. He saw the Big Ten brand living — not merely existing — in the world’s richest seaboard. The Big Ten could fill the collegiate vacuum from the Washington, D.C., suburbs through southern Connecticut.

“My view is if we could attract Maryland, we would be open to another institution,” Delany says. “That was Rutgers. AAU (Association of American Universities). Contiguous state. Penn State always has been a huge proponent for Rutgers. They always had done a lot of recruiting there. Our presidents wanted AAU.”

The Big Ten formally announced Maryland on Nov. 19, 2012, and Rutgers the following day. Rutgers, in particular, was not a popular move. Although the football team was 9-1 at the time, it never had played in a major bowl game and had finished ranked just three times.

Still, Delany saw potential. With Maryland and Rutgers, the Big Ten added 18 percent to its population and just 3 percent in land mass to its geographical footprint. As the official state university of New Jersey, Rutgers had access to government funding. Plus, the football stadium was located less than 40 miles from New York City.

“People can be critical of it. But I’m not,” Delany says. “I’m not defensive about it. I just think that overall, while it wasn’t North Carolina or Virginia or UCLA or Southern Cal, I think it took the Big Ten’s brand and dropped it in probably the most valuable corridor in the country.

“Maryland has won a football championship and a basketball championship and Rutgers is way behind. But Rutgers has shown that indication … You can’t make up in five years or 10 years for lack of investment, infrastructure-wise. I think they’re gonna be OK, but not in a five- or 10-year window.”

But to this point, the Big Ten brand has not elevated Rutgers athletics. If anything, it’s done the opposite.

Things started to go awry even before the Scarlet Knights played their first Big Ten game. In April 2013, athletic director Tim Pernetti, a key figure in securing the conference invite, resigned days after a troubling video surfaced of abusive behavior by men’s basketball coach Mike Rice. The school’s replacement, Julie Hermann, was accused of misconduct at Louisville and Tennessee and became a chronic public relations nightmare for the school, once telling a journalism class it would be “great” if the Star-Ledger newspaper folded, and making a Jerry Sandusky joke during a staff meeting.

Hermann was fired in November 2015, the same day as Schiano’s successor, Kyle Flood. After a respectable 8-5 debut season in the Big Ten in 2014, highlighted by a home win over Brady Hoke’s last Michigan team, Rutgers fell to 4-8 overall and 1-7 in the Big Ten the next.

The Scarlet Knights have yet to have another winning season. For the most part, they have not come close.

Since joining the league, they have the worst record in the Big Ten, with 10 fewer Big Ten wins than Maryland. Opponents have shut out Rutgers 14 times over that nine-year span, six more than any Big Ten team since 2000.

And it’s not just because Rutgers plays in the rugged East Division. Rutgers’ winning percentage against East opponents is .167. Against the West, it’s .160. The 66 conference losses are the second worst among Power 5 programs over that span (Kansas has 72).

Beginning late in the 2017 season and lasting through 2019, Rutgers lost 15 consecutive Big Ten games by a combined score of 734-164 (48.9-10.9 ppg).

“I had been there 11 years before I had left, and then I’d been away for eight years,” says Schiano, who returned in 2020. “I was a little bit shocked how much things had changed. And I’m not just talking about the athletes or the football, I’m talking about the infrastructure.

“So we had to really rebuild a lot of the things, whether it’s medical coverage, the way the players ate, nutrition, training, all that.”

Football carries the most prominence, but nearly all of Rutgers’ programs have struggled. Over the last six Directors’ Cup standings, Rutgers has finished last among Big Ten teams four times. A year after posting one of its best showings in decades (48th, 10th among Big Ten schools), Rutgers fell to 130th nationally this past school year, the third time in six years (not including 2019-20, when there were no final standings) that the school finished in the 100s.

“As you’re building your program, you’re going to have years that are up and down as you try to get to being a consistent winner and have consistent success,” Rutgers athletic director Pat Hobbs says. “In the Directors’ Cup, I thought our men’s basketball program deserved to be in the NCAA Tournament this year; obviously, that would have affected that score pretty significantly.

“We played really close in a number of football games, where — if for the sake of a touchdown or two the other way — we’re going to a bowl game again. Those two alone would have been credited with a significant number of places in the Directors’ Cup. And I’m pretty confident where we’re going this year.”

Nearly every Big Ten athletics department is self-supporting; Rutgers, however, is reliant upon funding from either student fees or institutional coffers.

Of the Big Ten’s 13 public universities, nine athletics departments receive minimal or no funding from the university, state or from student fees. However, over eight years of data, Rutgers has received nearly $240.8 million in direct university or state funding or from student fees. Maryland ($128.3 million), Illinois ($55.9 million) and Minnesota ($20 million) are the other three Big Ten schools receiving funding from those sources over that eight-year period. Minnesota’s athletic department gave back more than $2.3 million, Illinois’ gave more than $1.3 million and Maryland’s gave $620,000 to their respective universities. Rutgers has transferred back zero.

“The Board of Governors and the Board of Trustees know exactly what’s going on,” Killingsworth, the Rutgers professor, says. “The question (for them) is not, ‘Why are we spending so much of this effing money?’ The question is, ‘How can we spend more? What else do you need? We’ll give it to you.’”

Beginning in 2020, Rutgers athletics has reported more than $69.8 million in combined losses to the NCAA, per financial forms obtained by The Athletic via state open-records laws. An NJ Media investigation in 2021 documented $265 million in total debt.

Before it became a fully vested Big Ten member in 2020, Rutgers borrowed $48 million from the league against future earnings. The payback schedule remains undetermined as university brass works with new Big Ten commissioner Tony Petitti on a workable solution.

“There was a lot of propaganda about how the Big Ten was going to be our financial salvation that was going to make everything right,” Killingsworth says, “which even at the time, if you had a brain and a pencil and paper, and you could do basic math, the net increase in income, between leaving the Big East and arriving in the Big Ten, would not be enough to make up the deficit. And they just ignored that. They fell for their own propaganda.”

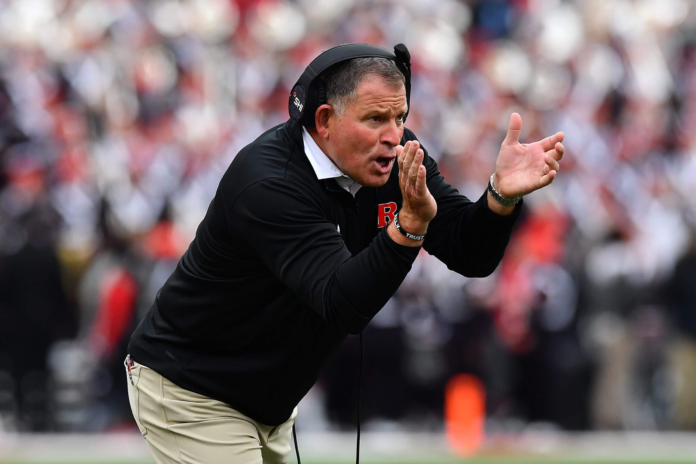

Schiano represents a Hail Mary of sorts to improve Rutgers’ financial profile. Four home games featured at least 51,000 fans last year, and the Scarlet Knights set a school-record average attendance of 50,756. The 55,676 that piled in for the Penn State-Rutgers game set a single-game record. Schiano’s popularity has spurred ticket sales, but with no luxury suites and limited club seating at SHI Stadium, there are few ways for Rutgers to generate revenue from the stadium.

“We’re somewhat hampered in that our football stadium has 53,000 seats,” Hobbs says. “Our Jersey Mike’s Arena has 8,000 seats. We have the lowest premium seat inventory, I think, in the conference, and we’re looking to change that.”

To Killingsworth, that type of thinking has put Rutgers in the current financial predicament.

“Every year, there’s a supposedly new solution,” he says. “They expanded the stadium, that was going to change the game, and then they hired Greg Schiano and that was going to change the game, but it didn’t. And then they had to hire him again, and that hasn’t changed the game. And they joined the Big Ten — and that’s actually made it worse, right?

“It’s sort of like the guy who thinks, ‘Well, I’m gonna get a raise next year, so I can go out and spend freely this year.’ You’re constantly chasing after next year’s raise.”

But while Rutgers has hemorrhaged money, the Big Ten’s coffers got richer thanks to one particular revenue stream – cable subscription fees. As of 2014, the Big Ten Network, co-owned by Fox, received $1 per month from cable providers within the conference footprint as opposed to around 10 cents out-of-market. Once it joined the Big Ten, Rutgers became an in-market school for the roughly 6 million cable households in New York, New Jersey and parts of Connecticut.

“We basically had a 400 percent increase (in network revenue),” Delany says of the Maryland/Rutgers impact. “We went from about $50 million a year to about $200 million a year annual average value. That makes everybody’s eyes pop.”

But the schools’ arrival coincided with the dawn of cord-cutting. BTN had 49.6 million subscribers in December 2022, a 9 percent drop from just a year earlier, according to Sports Business Journal analysis of Nielsen research. Meanwhile, in 2021, the conference sold a stake in BTN to Fox, which now holds 61 percent ownership. Cable revenue, while still significant, is not nearly the same revenue driver as the conference’s new deals with Fox, CBS and NBC, reportedly worth more than $1 billion a year.

That begs the question, does Rutgers still carry the same value it did then?

“Rutgers was a bad idea long term,” says a sports media consultant, who was granted anonymity to speak candidly. “At the time, it worked. But with the television model moving from cable to direct-to-consumer, they don’t deliver New York City. The network still has those carriage agreements, but that’s majority owned by Fox now, so their positive impact is shrinking.”

Another consultant, Patrick Crakes, a former VP at Fox Sports at the time it launched BTN, doesn’t see it so starkly.

“Pay TV is declining, but that doesn’t mean they don’t still have money to give to select properties,” he says. “The opportunity cost of not having Rutgers and Maryland is high. Adding all those residences in New York and D.C. helped convince providers to increase the value of Fox, FS1 and BTN. The opportunity cost of not having Rutgers and Maryland would be high.”

But when will Rutgers football give all those households reason to watch its games?

Rutgers football coach Greg Schiano’s popularity has spurred ticket sales, but with no luxury suites and limited club seating at SHI Stadium, there are few ways for Rutgers to generate revenue from the stadium. (Ben Jackson / Getty Images)

Rutgers’ men’s basketball success gives the football program — and the department — hope for improvement. The Scarlet Knights lost 31 consecutive Big Ten games in their first two seasons and were 9-63 over their first four years. But Steve Pikiell has resurrected the program competitively and turned Jersey Mike’s Arena into one of the Big Ten’s most challenging home environments.

In 2021, Rutgers played in the NCAA Tournament for the first time in 30 years. It has built four consecutive postseason-caliber teams, also making the tournament in 2022 and missing out in 2020 only because the pandemic canceled the event.

The momentum has elevated recruiting. Rutgers’ 2024 recruiting class ranks No. 2 nationally in the 247Sports’ men’s basketball composite with five-star and No. 2 overall player Airious Bailey, plus two four-star commits. The football program sits No. 32 in the 2024 composite recruiting rankings.

“We play in the best conference in America,” Schiano says. “So we have to build a program that can compete at that level and someday be a championship-level program.

“How do you do that? You do that one step at a time. You recruit the right players, and you develop them. To me, that’s it. … If we know who we are, we have to develop our guys and get them to the end of their career, where they’re playing their best football. That’s how we’ll win there.”

Patience with football is something Hobbs also preaches. Schiano is 6-21 against Big Ten competition through his first three seasons back. At times, the program looks competitive. In other games, it looks completely overmatched. The Scarlet Knights finished 1-8 in conference play last season, losing four of their last five games by at least 30 points.

“People knew who Greg Schiano was, and what he brought to the table when he came back,” Hobbs says. “I think he closed that challenge pretty quickly and then it’s a matter of you’ve got to put the time in and you got to put the years in of developing the players so that they can be successful.

“This is a big year for us coming up.”

(Illustration: John Bradford / The Athletic; photos: Michael Hickey, Rich Schultz, James Black / Getty Images)

!function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s)

{if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function(){n.callMethod?

n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments)};

if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version=’2.0′;

n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0;

t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0];

s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)}(window, document,’script’,

‘https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js’);

fbq(‘init’, ‘207679059578897’);

fbq(‘track’, ‘PageView’);

source